It’s been a productive year for Farrah Karapetian, a participant in “The Black Mirror” group show at the Diane Rosenstein Gallery, L.A. Louver’s 2013 “Rogue Wave” survey, and the 2013 California-Pacific Triennial at the Orange County Museum of Art. She has also been writing a Tumblr blog, Housing Projects, concerning the house “in and as contemporary art.” Although the blog at first seems not so different from similar online journals, its relation to her art practice is clarified by her first pre-photogram work and her most recent work.

It was her work documenting scarred and ruined architecture in Kosovo that ultimately led to her abandonment of conventional photography. Yet there is an uncanny continuity between these initial photographic essays and her most recent work, which are nothing less than photogram constructions of ruins. While nothing might seem more distanced from the implied cumulative marking, decay, and (conceivably) violence of a ruin, than photograms of melting ice, it might be recalled that the inspiration for Karapetian’s 2012 “Accessory to Protest” show was nothing more than a brochure that advised protesters of the “Eight Items of Necessary Clothing and Accessories” they might need in Cairo’s Tahrir Square.

Karapetian has always been preoccupied with the formal challenges involved in transposing the impact of a documented actuality to the viewer’s visual and physical encounter, as well as the transparency of her own process. There are also, latently, issues of instrumentality and indexicality. Making reference to a large installation photogram (“Riot Police” (2011) from her 2012 Roberts & Tilton show, “Representation3”), Karapetian commented, “[if you] stand in front of these riot police, you understand them physically.”

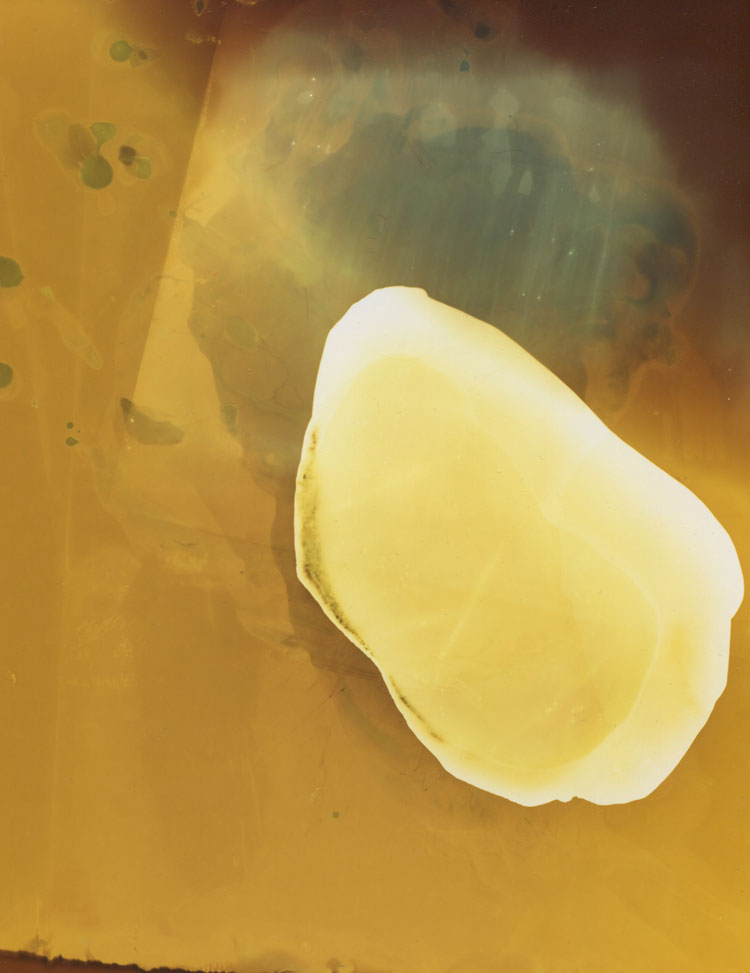

Melting ice takes the kinds of elisions between pictorial and sculptural space extensively explored in her prior work to still further levels of abstraction and ambiguity— a sculptural negative that might transition dimensionally from solid to gas, leaving almost infinitely varied random markings. But Karapetian emphasizes above all the temporal dimension. “It’s about time and how we remember things…” Addressing the abstraction of the OCMA “ruin,” “Rock, Paper, Scissors,” she observed, “There’s a built-in distance between the referent and the image. It’s supposed to look like a rock, but it’s ice. It’s not a photograph of a rock, but it’s acting like it is; but it’s also built like a puzzle”

There is a tension here between the randomness of the markings made by the melting ice in the photograms and the kinds of environmental, atmospheric and human markings they evoke, and the deliberation with which the 900 individual amber/gold photogram “rocks” are built up around an aperture in the OCMA galleries through which the viewers pass. It’s as if they were a recapitulation of a ruin yet to be discovered—or yet to come. Here, the architectural aspect of her work elides still further into the domain of performance; and the viewer is placed in the position of acting out a memory s/he can only begin to apprehend.

0 Comments