The saga of British art dealer Inigo Philbrick is testimony to the pitfalls of the trust and handshake deals that have become customary at the highest levels of the art world. The fall of Philbrick—a protégé of Jay Jopling, the principal of London’s most prestigious art gallery, White Cube—sheds light on fast and loose practices of high-flying dealers, such as buying and selling fractional shares in artworks and price guarantees at auction. Faced with at least three lawsuits involving him and his company, Philbrick has now fled to parts unknown.

Philbrick, 32, came to the art world with a fine pedigree: his father had been director of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut, his mother teaches at Parsons School of Design. Philbrick attended Goldsmith’s, University of London, an art school. Jopling, also a Goldsmith’s graduate, hired Philbrick as an intern at just 24 and within a year he was made director of secondary market sales at White Cube. He sought to go off on his own and in 2013, with financing provided by Jopling, he opened Inigo Philbrick Gallery in Mayfair where he also resided. Philbrick lived a flashy lifestyle sporting bespoke suits and expensive jewelry, and dating a popular reality TV star soon after his partner gave birth to his child.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2012.

Philbrick dealt primarily in secondary art market sales and specialized in works by Yayoi Kusama, Mark Bradford, Wade Guyton, Christopher Wool and Rudolf Stingel. He claimed to be an expert on Stingel and it would be his photorealist painting of Picasso that first got Philbrick in trouble. He bought the painting in 2016 for $6.7 million with his friend Sasha Pesko, who put up half the funds. Philbrick who was used to quickly flipping art, held onto the Stingel when he couldn’t get anyone to buy it for his asking price. When it finally sold at Christie’s in 2019, it only realized $5.5 million. After the sale, all hell broke loose when it appeared that Philbrick had sold an interest in the piece to buyers other than Pesko. According to The New York Times, the other investor in the Stingel was Fine Art Partners, which had previously invested with Philbrick in works by Wool, Guyton and another Stingel. But the market for these three artists declined and Philbrick could not make quick flips of their works.

According to the Times, Philbrick showed Fine Arts Partners a guarantee by Christie’s on the Stingel painting for $9 million. After the disastrous sale, Philbrick assured them that Christie’s would make up the $3.5 million deficit because of the guarantee. When the money was not forthcoming Fine Art Partners contacted Christie’s, which examined the guarantee document and determined that it was probably a forgery. Then things got even worse. Christie’s general counsel told Fine Art Partners that Philbrick was acting as a representative of Guzzini Partners, an art investment company controlled by the Reuben brothers, renowned art collectors and one of the UK’s richest families. According to the Times, it turned out that Guzzini paid Philbrick $6 million in 2017 as part of a group sale including the Stingel. To top it off, the winning bidder at Christie’s was a dealer who was bidding at the direction of Philbrick to protect Pesko’s interest. The dealer paid Christie’s only $2.35 million and Philbrick failed to pony up his share of the money.

Philbrick had opened an art gallery in the Miami design district. That was the venue where Fine Art Partners filed suit against him. On the day he was due in court, his lawyer quit the case. Philbrick did not appear and has not been seen since. His Miami gallery was padlocked.

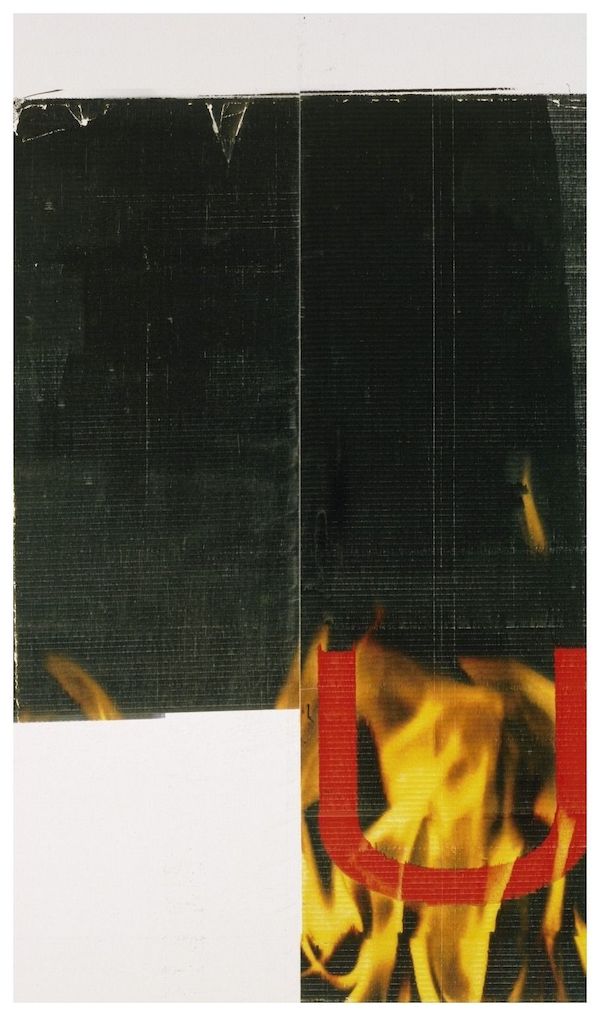

Wade Guyton, Untitled (Flaming U, Red U, Yellow Flame), 2011

The Times reported that with Philbrick on the lam, the Reubens brothers, through their company Guzzini, sued the Stingel painting “in rem,” (an action to determine rights to property) asserting that their claim took priority over the interests of both Pesco and Fine Art Partners.

At least two other lawsuits pending involve Philbrick, one by Pesco filed in London concerning a major Basquiat painting that Philbrick allegedly sold twice, the other concerning a Wade Guyton painting, “Flaming U,” against the Reubens’ company Guzzini by another putative buyer.

This is the sad tale of a high-flying art dealer who thought he could take advantage of the frenzy among the wealthy to flip art. The problem for speculators is that when they buy fractional shares in an artwork, they usually do not take possession, giving rapacious dealers such as Philbrick the incentive to conceal the actual amount of investments in the work. It’s estimated that Philbrick’s schemes have cost art investors well over $100 million.

Brilliant writing Mr, Goldberg!