When I first saw Marie Thibeault’s hybrid landscapes that merge abstraction with representational figures, I was struck by her bold use of color and unusual iconography, in which organic and industrial shapes are combined, many inspired by the Port of Los Angeles near her home. While the underpinnings of her work suggest eco-destruction amidst the natural environment, her completed paintings become exquisite, harmonious renderings that transcend the dystopian society we live in.

A visit to Thibeault’s 100-year-old home in San Pedro entails negotiating two expansive bridges with views of ships, shipping containers, cranes and birds. This journey enables one to experience the environment that Thibeault draws inspiration from. She has for years combined and layered details of these observed images into her paintings. And while she depicts these influences semi-abstractly, she regards herself as a landscape painter.

Thibeault in her studio, photo by the artist; courtesy of the artist.

When I arrived, we began by walking through the home she shares with her husband to her backyard studio. The light-infused space is filled with her paintings, drawings, color charts, books, tubes of paint, art books and computers needed to teach painting and color theory Zoom classes at Cal State Long Beach (where she has taught for three decades).

In the comfort of her sprawling studio, Thibeault discussed her early life, growing up in Baltic, Connecticut, a rural town in the state’s eastern end. “My French-Canadian parents were not artists,” she says, “but they were artistic.” She was influenced by visits to the nearby Slater Memorial Museum, and its New England landscape paintings. Viewing these masterpieces inspired her lifelong love of landscapes. “By the eighth grade, I knew I wanted to be an artist,” she said.

Thibeault attended a nearby art school where she studied drawing and painting. She also learned about the work of the masters, including Paul Cézanne, known in part for his horizontal planes. “The picture plane in his work is moving and breathing as space that moves,” she said. “I learned to paint like Cézanne.” After graduation, she attended the Rhode Island School of Design, where she received a BFA in painting, and later earned her MFA at UC Berkeley, studying with Elmer Bischoff and Joan Brown.

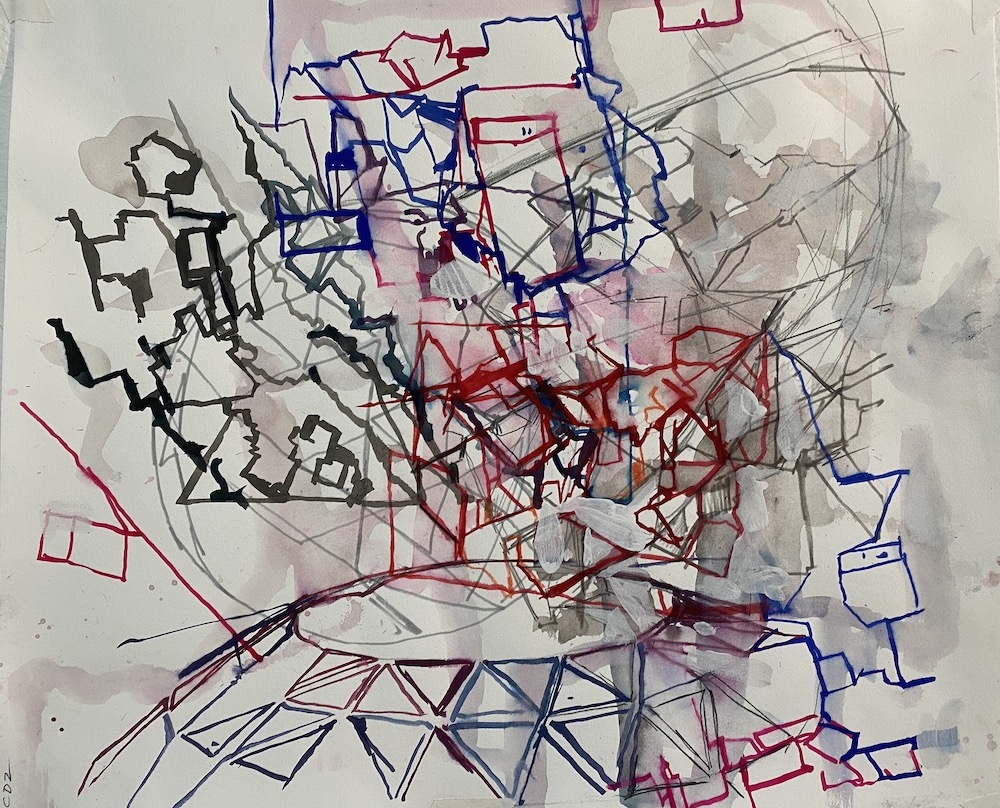

Marie Thibeault, Covid drawing group 2, 2020

She moved to San Francisco in 1979, soon afterward immersing herself in environmental movements. The initial impetus for her green consciousness was the proliferation of aerial photos of disasters in local newspapers, “especially pictures of plane and train crashes and nuclear calamities such as Three Mile Island.” She began using these aerial photos as inspiration for her paintings, and continues to do so. Among the disasters she has depicted are Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. “Destruction is the pivotal point of change,” she explained. “There is tension between instability and balance, breakdown and recovery.”

Thibeault directed my attention to specific paintings in her studio, several containing “horizon lines.” She begins each piece by drawing and stenciling abstract industrial and natural images, many of them birds, onto the canvas. Working intuitively, she expressively applies bright primary oil paint, balancing these colors with muted hues. The results are semi-abstract, harmonious landscape-influenced works that explode with color. Two such recent paintings are Shield (2017) and Moving Cities (2018), both containing deep blues, greens and black, with obscure, densely painted imagery, referencing ruination in the environment.

Marie Thibeault, Gravity’s Angel, 2019

The artist then showed me numerous drawings she began in March at the start of the lockdown. “I was blown apart by the pandemic,” she said, “and stuck at home teaching on Zoom. I was depressed and all I could do was draw, so I did three to four drawings a day.” While their shapes and forms echo those in her paintings, these drawings are more abstract and include medieval illustrations, astrological maps and ancient diagrams illustrating serpents, insects and birds. “They also use diagrammatic forms referencing global mapping and scientific charts,” she said.

Thibeault recently began saving medieval imagery from the internet and plans to employ these symbols in her future work. She explained, “With the current global pandemic and the effects of climate change, we are so much in the dark. And with many people embracing the type of superstition prevalent during the Middle Ages, these millennia-old images are particularly relevant to me.”

Sitting erect on a stool, Thibeault added, “Just as we turn to science to help us understand forces beyond our control, I am widening my view in my paintings to include a sense of global space and interrelationships, creating complex spaces with a sense of deep time, connecting the present to the past.” While her next paintings will continue to include environmental influences, they will aspire to further connect people to their surroundings and to each other, addressing what she describes as, “the tension between instability and balance.”

I am fascinated by Marie’s use of ancient imagery within a contemporary context addressing very pertinent issues as we all struggle to live through the COVID-19 experience.