It’s a typical Saturday night, the drinks are flowing and the music is playing – as I lie in the bathtub reading another David Goodis novel, sipping another tequila and soda, with a Brahms piano sonata playing softly in the next room. I’m in my natural element, enjoying an experience I have had thousands of times before. But something feels different. What’s missing is a slight shadow that would normally be cast over this idyllic scene in the form of dreading an imminent social occasion or lamenting the lack of one, and, yes, perhaps morbidly considering the prospect of other people enjoying themselves.

Now that nobody does anything anymore, this phenomenon, otherwise known as FOMO, has thankfully become irrelevant. Such futile concerns can no longer pollute the pleasures of balneation: I can luxuriate in watery repose for as long as I like, without having to endure any vain gnawings about what I’ve been included in or excluded from, then spend the rest of the night catching up on Deadwood.

I’m not the first person to point this out (I’m probably not the first person to have pointed anything out) but one of the most welcome things about this stay-at-home ordeal/ ideal is the refreshing absence of social pressure. We’re all alone in this together, amusing ourselves in the privacy of our respective homes, in what, optimally, is an extension of the most rewarding aspects of our usual lives. As Madonna opined from the fragrant confines of her own petal-strewn bathtub: Quarantine is a great equalizer.

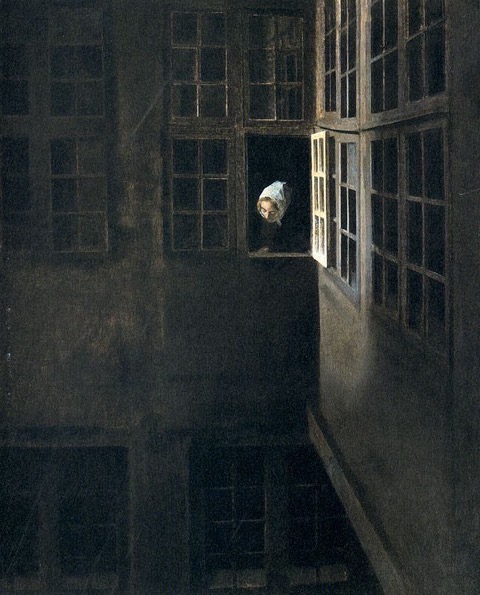

Pierre Bonnard, Nude in the Bath (1925)

There are new pressures, certainly, but if one can set aside for a moment such matters as death, poverty, and the sudden unraveling of life as we know it, this is a very pleasant reprieve from routine. For the time being, there are no deadlines, other than that biggest of all deadlines. The natural rhythm of existence has been restored, and this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to relish it. The long-term political consequences and ramifications aren’t going to be pretty but it’s only going to get worse, so you might as well enjoy the calm of this cloistered springtime before the rot of summer sets in and things get really nasty.

As John Peel said of the Fall: “Always different, always the same.” So it goes with these days that blur into each other as they drift by in varying shades of anxiety and serenity, without much in the way of work/play obstacles to break the flow.

It’s the unbroken solitary rhythm that becomes so seductive and seems to awaken a certain spirit of receptivity and productivity. Solitude seems to be a blessing, and I fear for the well-being of my cohabiting friends, cooped up in happily married misery, some of whom, unfortunately, haven’t been faring too well during these trying times. And they might pity me in my supposed loneliness. But under these potentially claustrophobic conditions, solitary confinement seems preferable to connubial captivity – better to just get on one’s own nerves. It’s apples and oranges, of course, but personally I have always preferred apples: they’re sweeter, less messy and they don’t take so long to peel off.

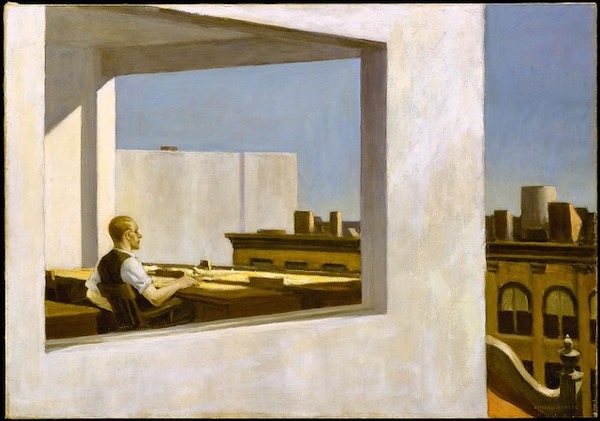

Vilhem Hammershoi, Interior Of Courtyard (1899)

Forty nights straight at home alone. This alarming and previously unthinkable figure is somehow made tolerable by the non-hierarchical quality, which takes the edge off. In this unifying isolation the telephone has reverted to its original purpose as an instrument of spoken communication. It’s pleasing that it’s being used the old-fashioned way, and that old friends are reaching out. The only downside is that one can’t pretend that one isn’t home anymore, and it can get overstimulating: somebody is always restless, and only one subject is ever under discussion. Phone fatigue is a real thing, but one can’t really complain about it, because next time yours might be the voice of lonely desperation on the other end of the line.

There is a lot about these times that will be looked back on nostalgically. Never again will one be able to savor the ghost town-like tranquility that permeates every early evening with an exquisitely alien stillness. And if by chance one does spot somebody one knows on the street, it is now socially acceptable, even desirable, to walk away from them. No tiresome exchanges with annoying acquaintances, no awkward hugging or clammy hand-shaking. What could be better? It’s a new form of freedom. There are some definite positives to take out of this new unreality, and I haven’t heard much complaining from anybody.

I know that I will miss these days when they’re gone, and that I won’t be alone in doing so. Out of this seductive seclusion a new routine has emerged, and I don’t have much desire to break out of it. Another month or two of this, however, will truly put resilient introversion to the test and sort out the lonely wolves from the restless sheep.

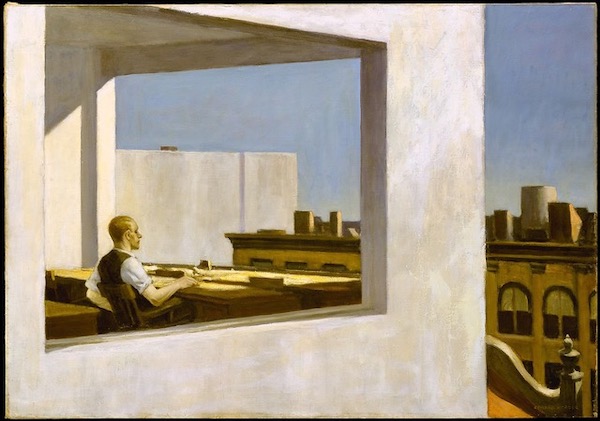

Edward Hopper, Office In A Small City (1953)

The silence sizzles, the dissolving soap bubbles float listlessly, the glass is emptied of its remaining drops, the plug is pulled, and I watch the tiny tornado funnel of water cast its shifting shadows around the drain. It is time to get out of the bathtub, make a few phone calls, and attend to the taxing business of sorting through my old collection of cassette tapes.

The most challenging part of all this is going to be the return to the old normal, compounded by all its daunting uncertainties. The prospect of going out again already seems strangely oppressive, while staying home all the time won’t feel natural anymore. I suspect that once ordinary life is resumed, there will be an emptying effect. It will have to be embraced gradually and handled very carefully. I am already dreading it.

Yes me too, already preemptively missing it. How could I ever imagine than my neighborhood could mimic the evening soundscape of a Calabrian village!? Must savor it.

I dread the hanging chad of social responsibility.

Tottenham always says it best.

Can you come over for dinner tonight?

Nice piece, Tottenham. Its a good time to be an orphan.

Perfection

Ha! Ja! Great piece. Meanderless John.

But am I not supposed to feel guilty bout relishing this stand-still?!

I guess I could chose to do so. Oh… right : why?!

Made me feel as if I was in the tub with you! Sweet.

Meandering ego running on….Great paintings!

“Strangely” oppressive?

This very John Tottenham.