No wonder your president has to be an actor. He’s gotta look good on television.

Emmett Lathrop “Doc” Brown, Ph.D.

Back to the Future, 1985

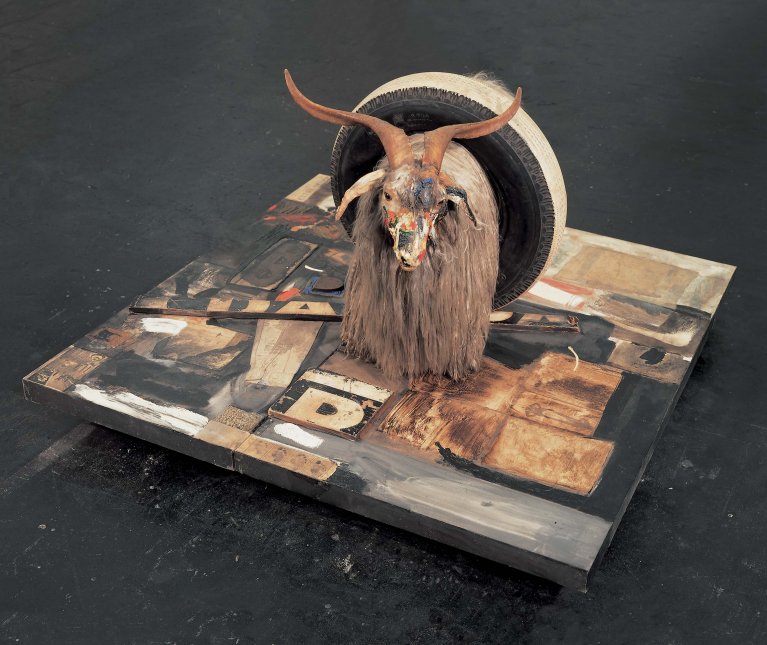

It stands triumphantly—a voracious junkyard goat surmounting a catafalque of the written word, a bier of gibberish, a babel of ancient symbols. Pen pals, gone; cursive gone, love letters now exchanged in childish icons. Having eaten everything we said, consumed everything we heard, it has trod upon the leftovers and smiles, faced rouged like a drunken courtier, still hungry. It took four years, an entire presidential term, for the goat to finally surrender its meaning but since then, 60 years and counting, it has done nothing but reiterate its prophecy.

While Cold War paranoia was a fog that settled upon nearly every aspect of American life, from the modernity of its kitchen appliances to the quality of its rocket ships, one aspect of U.S. culture was irredeemably doomed despite educationalist fist-shaking and hosannas to its import—the American literacy rate. Invisible Soviet chicanery or celebrity Hollywood pinkos did not doom Johnny to illiteracy; it was a homegrown and eagerly awaited advent, and Vice President Nixon, although he didn’t know it at the time, was its turning post.

But he should have known better.

He was a cautious and successful poker player, and a decorated war veteran—just like his upstart rival if not so gaudily decorated. While some people were convalescing, writing books and winning Pulitzer Prizes, Richard Nixon was dutifully fulfilling his obligations in the senate. And had he not been Vice President of the United States, a heartbeat away from the most prestigious position on the planet? How could he lose? Although he knew not to underestimate his opponent he measured himself against Kennedy, honestly and soberly, and saw that on every metric of suitability for the nation’s highest office that he, Richard Milhouse Nixon, was the more prudent presidential selection. And that the debate between the two candidates would take place on a live television broadcast assured Nixon that the American people would be able to make a choice based upon the merits and experience of the competing candidates. He had full faith in the intelligence and fairness of the American people. This was not the high school debating society from which the rich kids had barred him, this was the serious business of the greatest country in the world. Nixon was no stranger to television. He had confronted and defeated suspicions of financial dishonesty with his televised speech about his everyman bona fides, his wife’s cloth coat, and their distinctly non-kennel club dog, Checkers. He had even bested Nikita Khrushchev on television.

While it would have made a fine coat, one that Mrs. Nixon might have worn quite smartly, Robert Rauschenberg’s goat was meanwhile giving him fits. In the various iterations of Monogram (1955–59) Rauschenberg sought to elevate the angora goat—spotted in an office supply resale shop—to a component in one of his combined artworks but struggled to find an appropriate usage. The goat was too much itself and would not surrender its aura. “First, I tried to put it on flat plane, it was obviously too massive. It had too much character. It looked too much like itself.” Then was a drawing of a vertical plane with the goat raised and placed transparently behind a ladder, with the painting behind. No dice. It then had been hoisted and hung on a shelf attached to a painting, like a hunting trophy on the wall; he removed it and let that painting live a life of its own as Rhyme (1956). “So I took it off the wall, put it in the room and built a (narrow) upright panel, but then it looked like he was a beast of burden. He kept looking as though he was supposed to pull it.”

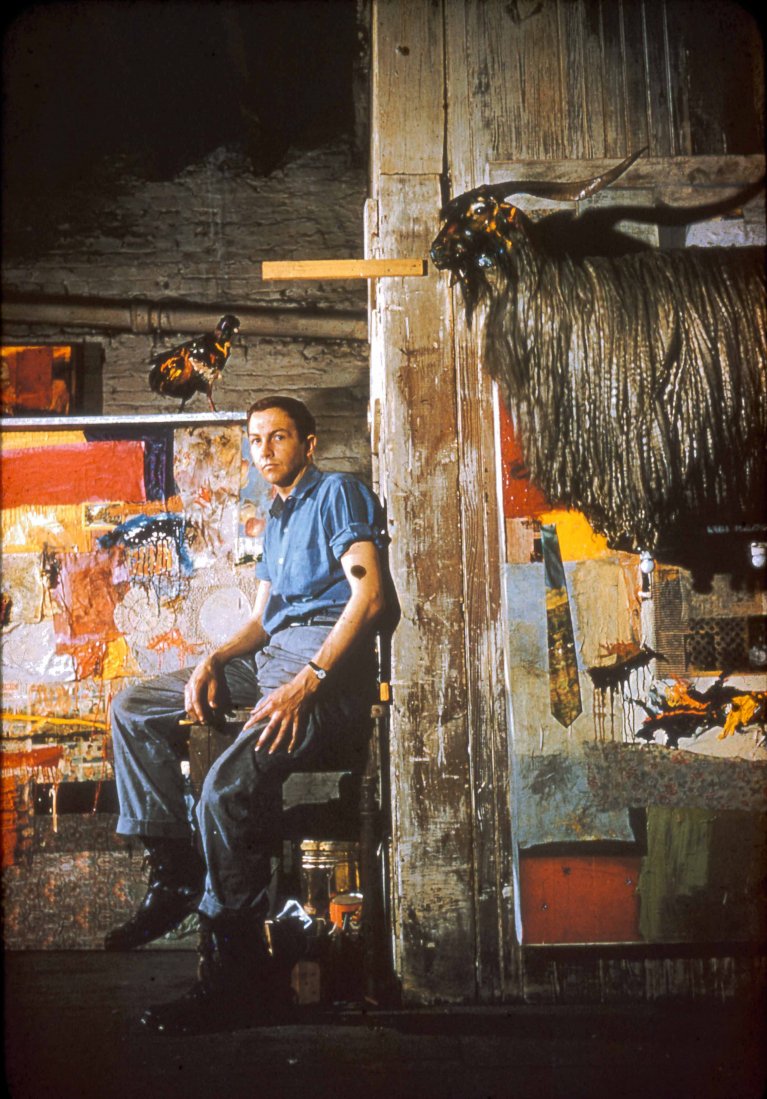

Rauschenberg in his Pearl Street studio with Satellite (1955) and the first state of Monogram (1955–59; first state 1955–56), New York, ca. 1955. Image courtesy of the Rauschenberg Foundation.

The presidential contest was also a struggle. On substance, the debates were neck and neck. Nixon had significant White House experience and was a knowledgeable attorney. But he had been ill. After two weeks in the hospital, he was some 20 pounds underweight; he looked pale and weak. While the Museum of Broadcast Communications allows that on the substance the debates were extremely close—radio listeners called it a draw—the 70 million viewers who tuned in by television could not have avoided noticing Nixon’s sickly appearance. Still recovering from the nasty infection in his knee, exhausted by a speech to a labor union earlier in the day, and refusing the cosmetic essentials offered repeatedly by television professionals, Richard Nixon looked less like the man who indicted Alger Hiss, than the reputed communist himself. It was a disaster. Nixon recovered, less exhausted and wearing makeup for the three subsequent debates, but it was too late, by then he looked as if he were a trickster, despite woolen coats and fluffy dogs. Advantage: Kennedy, 49.72% to 49.55%.

Nixon hadn’t lost because he was unprepared for the debate; on the contrary, he was eminently qualified for the job. His next step should have been the oval office. His loss was a matter of style over substance. His expert words were tainted by his inept appearance. And as countless grandmothers have told youngsters again and again, one never gets a second chance to make a first impression. His first impression as a candidate was a failure not because of words but pictures. Words had become subservient. It was a bitter lesson that Nixon would not forget; eight years later it was his presidency that established the White House Office of Communications, a professional media operations division, with television as its prime concern.

This should come as no surprise. The advantage of pictures over words was already clear. The written word. The spoken word. William Conrad, who was a sinister standout presence in the Burt Lancaster films The Killers and Sorry Wrong Number, was for a decade the star of the hit radio series Gunsmoke. But he did not make the transition to television in 1961; too short, too portly, too balding. The role went to the less talented but better looking James Arness, who played the space monster in the classic sci-fi film, The Thing. While the cinema required us to remove ourselves from our homes the television indulged our tendency, even preference, for indolence. And, so that we didn’t miss a thing, we even invented provisional furniture to replace the dinner table so we would not let slip a moment. It was a trend with legs. Our growing physical indolence—the average American man gained 30 pounds between 1960 and 2017— paralleled our intellectual torpor; by 2017 Americans were averaging 166.2 minutes per day watching television, outpacing their reading time—16.8 minutes—by nearly a factor of 10.

Monogram, like Nixon, was initially passed over. It was first shown in 1959 by Leo Castelli Gallery. Robert Scull, New York taxi king and noted art collector, was so impressed and certain of its iconic future that he suggested it should immediately be accessioned by the Museum of Modern Art. He would buy the work himself for the collection. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., director of MoMA and author of the white-cube exhibition aesthetic, was less impressed with the work and the offer. Now, one the most important works of postwar American art makes its home in Stockholm, at the Moderna Museet.

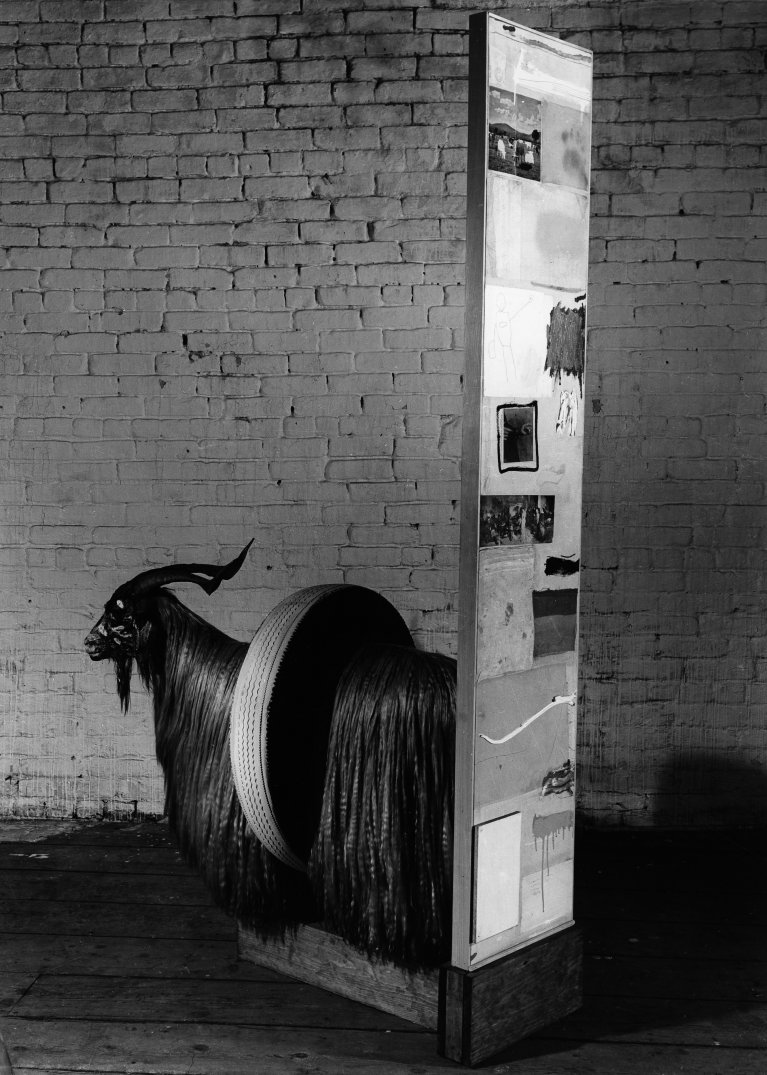

Second state of Rauschenberg’s Monogram (1955–59; second state 1956–58) in his Pearl Street studio, New York, ca. 1958. Photo: © 2013 Estate of Rudy Burckhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The postwar economic boom fueled job growth and with it, product purchases. While in 1947 there were just 14,000 televisions in America by 1962, 90% of American families owned one; some 56 million homes. In order to finance content for all of the programs on all those televisions Madison Avenue dutifully supplied the advertising. They sold the products that sold the programs. They were the purveyors of entertainment by way of marketing and their contributions to the medium of television were nearly as important as the characters in the programs themselves. Everyone profited from television—the actors, the sponsors, and the advertising executives but it was the clever ad-makers who fired a consumer culture that kept America spending by telling us what to buy. They had become economic soothsayers. These Madison Avenue hotshots wore the Madison Avenue look and one haberdasher was particularly preferred, Brooks Brothers. Midtown, Uptown, Downtown, the iconic brand was omnipresent in Manhattan and their ancient and now legendary logo, as clothier to ivy leaguers and presidents, was readily recognizable. The Brooks brothers had stolen it, of course, in order to give themselves an instant pedigree but as the mediaeval Duke of Burgundy who started the club was not using it (dead for the last 403 years) there was no need to find a cash-poor Count willing to sell his title. Why not just take it? They did. In this way a man and his counter-jumping sons invented on-the-spot ancestry for themselves and became suit sellers to the soothsayers. It was Philip the Good who had in 1430 founded the knightly Order of the Golden Fleece—its symbol a golden ram suspended from a chain of order—and the wool merchants guild had used the symbol first anyway, since 1182, albeit without the ribbon.

Both Rauschenberg and his colleague, friend, and partner, Jasper Johns, both featured texts and objects significantly in their works and the Brooks Brother’s logo, the lamb suspended by a ribbon, as if a baby hanging from the bill of a stork, was already iconic. Brooks Brothers was by then 147 years old and founded just a mile away from their Front Street studios. With their Gatsbyesque cash-flows the admen were media princelings and needed the clothes befitting their station. What better badge could signal their arrival.

Rauschenberg, with his eye attuned for media imagery, could hardly have been unaware of the smart gents sporting the lamb logo, or the dozens of billboards featuring the suspended bovid and it was through this that his problematic goat-in-the-studio mystery had been solved, the hirsute horned creature would become his contemporary golden calf; un-look-away-able, ready for worship. The horizontal plane, that he had previously rejected, returned. It now made sense. No incised tablet, however sacred, could take the place of this ravishing golden-haired beauty. No words would ever upstage it. Let it stand upon the painted word, ready for its star turn. Like the Hollywood royalty who now gave us audience in our living rooms, Rauschenberg—like Brooks Brothers—awarded himself, and us, the Order of the Golden Fleece. He girdled the goat with a tire, for by then it had become gospel that what was good for General Motors was good for America, and upon the collaged and painted deck with discarded remnants of movable type it became another kind of beast, inviting and reveling in our gaze, surmounting print—words now subservient to images. Elevated. Historical. Mythical. Mercantile. Ever ready for its closeup. The passing resemblance to Satan was added value; better the devil you know.

Shortly afterward, in California, an actor began dabbling in politics. When his new hobby began conflicting with his television day job, as host of General Electric Theater, he retired from show business. A handsome man with a personable delivery, he was not idle for long. Four years later he was elected Governor of California.

I find this a real stretch. The Golden Fleece part. Brooks Brothers NEVER advertised their golden fleece symbol. That was the point of BB. Low key. No flash. Tailored to be non-tailored. BB would never call attention to itself.

RR may have known about the Golden Fleece from his own BB purchases, but not from media sources.