Think about the differences between the long-standing practices of painting and sculpture, and clichés persist: Painting is “flat,” sculpture is not; paintings go on a wall, sculptures do not. In contemporary art these separate paths often intersect; some notable mid-20th century examples being Jasper Johns’ encaustic and plaster paintings, Lucio Fontana’s stabbed canvases, Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines and Lee Bontecou’s wire-and-fabric wall sculptures. Try to determine the edges where one medium leaves off and the other begins, and you end up in a circuitous thought process.

Right now contemporary painting is having a sculptural moment. Florian Schmidt, who builds holes into paintings using cardboard and canvas, and Katharina Grosse, who sprays paint on a grand scale, are challenging assumptions about painting’s supposed non-relationship with real space. Some of the most intriguing experiments in painting are happening in Los Angeles. Dianna Molzan reconsiders a painting’s structural components by revealing the wooden framework, fitting stretcher bars with canvas sleeves and horizontally slashing stretched canvas until it sags. Matthew Chambers takes apart “failed” paintings and cuts the encrusted canvas into strips to wrap around stretcher bars. These new works are characterized by radial patterns and highly uneven surfaces. He takes a similar approach with clean canvas, coating the stretched strips in a solid color with automotive paint, or other glossy materials that can cause the strips to curl for a multidimensional effect.

I recently asked Chambers and seven other mostly LA-based painters who work sculpturally about what they do. Painters seem especially loyal to the rules of the medium, even as they venture into territory occupied by other media. They speak a language that demonstrates their intimacy with formal principles governing composition, color and even dimensionality. They must consider the real or metaphorical “wall,” that key presentational element that communicates “painting” to the viewer.

So what happens when any element or rule is upended? Does that change what makes a painting? “Painting probably does require paint, or at least some paint-like substance,” says Steven Wolkoff. (I agree, but secretly make an exception for Bontecou’s paint-less sculptures.) Wolkoff writes with paint squeezed from a pastry bag to form thick, matted layers across a canvas, or individual words to be gathered into sculptural piles that are loosely inspired by Anish Kapoor’s mountains of dry pigment. Wolkoff’s words and phrases have a conceptual purpose by referencing cultural touchstones in art, film, social media. Acrylic paint is often used in his work.

Stretcher bars, canvas, that rectangular shape on a wall; what happens when you take those away? Does that change what painting is? The answer I hear back is that none of that is critical. Like Wolkoff, Margie Livingston makes sculptural objects from acrylic paint, which she thickens with a gel medium. She pours and pools it into swirls of color. Once it dries, she takes the highly elastic skins and folds or drapes them. Other works are carved from dry chunks of paint into remarkable shapes. Livingston says of her process: “I’m playing with the weight of paint, letting gravity reveal the material’s flexibility.”

Linda Stark also talks about paint’s properties, but employs the slow-drying medium of oil. “Oil paint has a way of catching and reflecting light, especially on a three-dimensional surface,” she says. Her evocative jewel-colored paintings can take years to complete as she applies layers of translucent glaze, sometimes choosing to embed plants and dead insects. Stripes of built-up paint can radiate from a central knot or form a weave, with drips of paint extending the painting’s design beyond its edges. She says of her initial inspiration: “I was influenced by the industrial storm drains with their mineral buildup, near my downtown LA loft. I was drawn to explore the natural gravity and fluidity of oil paint, its tendency to drip, the way it builds up over an extended period of time.”

Time, especially “geological time,” is an apt metaphor for Laura Moriarty’s process and the conceptual premise behind her painting/sculptures. She works in encaustic (pigmented beeswax) to make striped and marbled objects that in a striking way resemble land formations. She casts shapes by slowly building up striations of color, then reworks them by fusing, carving, incising and chiseling; “excavation techniques” that suggest the physicality of land-shaping forces. For her, this fourth dimension of time has more meaning than any sculptural concerns.

“Painting can be determined by intention,” says Leanne Lee. “My intention is always to create a painting and to think as a painter, even if the outcome may resemble a sculpture.” Lee’s free-form shaped paintings can seem like they float on a wall, even though they are built of heavy plywood and are often huge in size. Across their surfaces, colors swirl and, in select areas, plant-like patterns pop up in relief. Up close you notice that this cake-frosting-like ornamentation is entirely made of paint. She applies a similar technique to freestanding sculptural pieces made of found wood.

Intention also explains the dimensional, shelf-like structures that Christopher Mercier builds to support thick applications of dried and wet paint. Some are relatively simple, like the three-sided “helmet” in which you might place your head for viewing. He also builds wall-length pieces with tilted panels. Strategically placed mirrors extend the metaphor of spatial illusionism. Mercier says: “A painting needs to address the issue of image making, which for me isn’t really about paint first and foremost—it is this ground or stage that viewers recognize as a space in which they can find painting.” Which explains why his newest piece is so large that you can literally walk inside it.

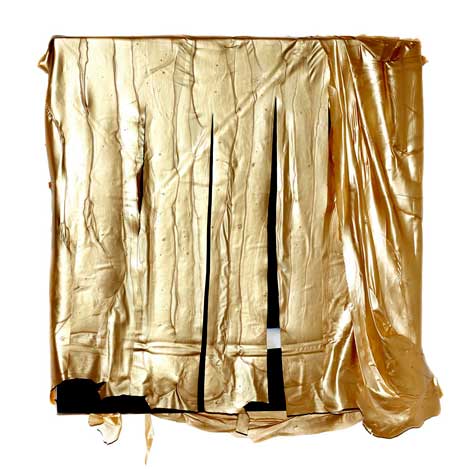

To most of these artists though, the fiction of the window doesn’t matter. Maya Lujan’s paintings do entertain the concept of spatial illusion but then playfully reject it. This is most apparent in works that feature thick skins of dried paint attached to the top of a canvas. These flaps of paint extend down, often past the canvas and even to the floor. And they can also obscure that prime image area, the front of the painting. In one series, the paint strips deliberately evoke stage curtains; in other works, those long car-wash sponges. “When I paint, I let the paint stand on its own and reference itself through sculpture,” Lujan says.

I ask these artists if and how they incorporate the tradition of sculpture. “I like to use materials that are typically associated with both practices,” says Lee. For her this means incorporating chicken wire, mesh, foam, rope and wood. In general though, how these artists work with paint—paradoxically—is what led them toward sculpture. Mercier, an architect by trade, might use a construction trowel rather than a palette knife or brush. Then there are sculptural processes like casting. Livingston uses techniques to manipulate dry paint that resemble what sculptors might do to clay or stone or metal. “I fold, cut, drill, saw, sand, tack, twist, roll, glue, stack or otherwise shape it,” she says. And then there’s the presentational aspect: the reality of sculpture as a stand-alone object. “Paintings can embody the same presence as sculpture, where one can consider the physical interaction of the viewer,” Lee says.

Margie Livingston, Folded Painting with Blue, Orange, and Pink, 2014, photo by Richard Nicol, courtesy Luis De Jesus Los Angeles

For most of these artists, it isn’t a question that painting can simultaneously be a sculpture and vice versa. Works of art can borrow from various disciplines. “Sometimes you find pieces that really do live in that middle ground,” says Mercier. By fearlessly experimenting, by throwing aside rules, by thinking sculpturally, these artists reframe our expectations about what a painting is.

I’ve been combining a painting process with a sculptural one for 20 plus years. I work primarily with an encaustic process that duplicates the archaeological excavation theme I explore. I overlap painting with sculpture and images of past with present time and culture, to emphasize my understanding of the ephemerality of life, art, and memory. Wax can be both painting and sculpture, so it serves as medium, process and dimensional form.

Slight correction: I am always adamant about not using canvases. Too bouncy, too flimsy. The wood panels that I refer to as substrates provide the kind of weighty support that is critical to the taction of the work. Also, of great importance, is that the paint is never attached from a separate location, it is always affixed and integral to the substrate. Thank you!