Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.

— Claude Cahun

Thinh Nguyen is a non-binary artist who calls our attention to the constructed nature of our ideas about race and gender. Nguyen challenges the dualist thought that dominates so much of our public discourse: the fraught oppositions of fixed cultural categories such as male/female, straight/gay, “real American”/immigrant, we/they (i.e., “those people”), etc. In doing so, the artist urges us to move beyond limited historic concepts of personal identity.

Nguyen was born in 1984 in a small village in central Vietnam. The child was quite ill and his frightened mother went to a fortune teller for help. The psychic said that they needed to “cheat Death” by disguising the child as a female. For his first nine years, Nguyen wore dresses and learned to behave as a girl. Eventually, Death moved on and the family could treat Nguyen as a boy. Soon thereafter, the family immigrated to the United States and the male/female/male child was forced to change national identity as well.

Nguyen’s educational quest was peripatetic, moving from psychology to painting to art education to receiving an MFA in studio practices from Claremont Graduate University in 2011. Since that time, the artist has developed an art practice shaped by research and “a series of revelations.”

Fundamental among these revelations was Nguyen’s awareness of non-binary sexuality. Not identifying as simply male or female, Nguyen rejects the pronouns he and she, preferring the new pronoun “xe.” (The artist notes that “xe” is Vietnamese for “vehicle” and the body is our vehicle for consciousness.)

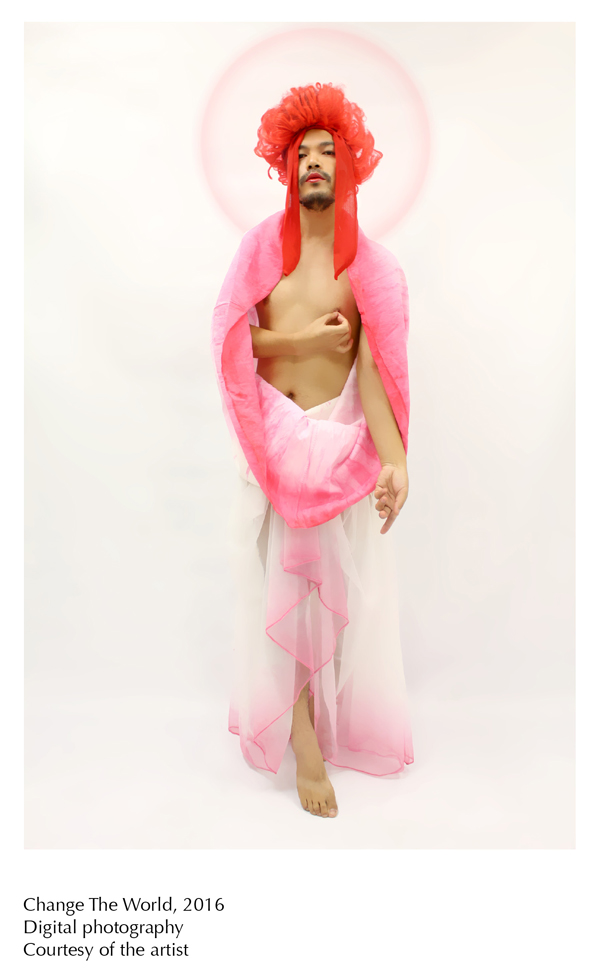

Nguyen performs non-binary identity in the female persona of Long Long. The artist appears as Long Long in order to “excavate oppressive cultural values and embrace femininity.” Xe disrupts racial definitions, becoming “white” with an extravagant white wig, long white dresses, and—in posed photographs—a thin white halo. Long Long sings what xe calls “protest mantra-songs” composed “as a way of personally dealing with and resisting against the current [governmental] administration.” In doing so, xe recalls Marcel Duchamp’s notorious Rrose Sélavy, a female alter-ego the French artist generated to explore gender identity in the 1920s. A second historical precedent is Duchamp’s avant-garde colleague Claude Cahun, who photographed herself as both male and female, claiming to be “neuter” or a member of the “third sex.” Nguyen goes beyond their explorations to bend both gender and race lines with Long Long. As xe explains, “Long Long emerged out of the realization that Western art history is not my history, my assigned gender is not my identity, and my identity is not a product of my cultural values. Long Long is my performance in power, in hope of altering the power relations and finding the threads that connect us all.”

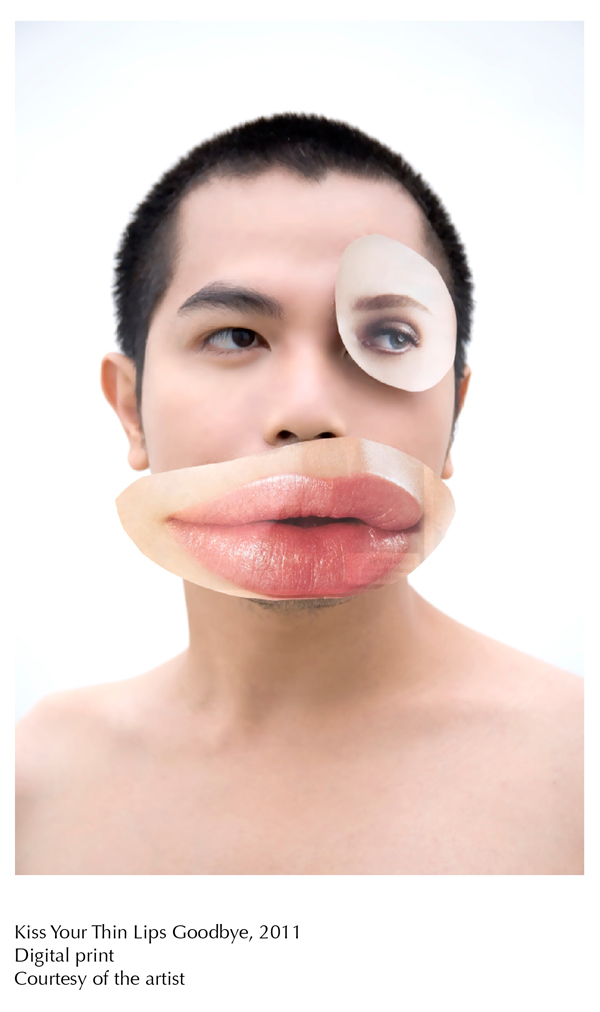

Nguyen’s Self-Imposed series was inspired by conversations xe had with Vietnamese women who said they wanted to be “white” so they could be “beautiful for their husbands.” Xe took self-portraits, bleached the skin white, and added collaged sections of supermodel photographs: thick lips from one, blue eyes from another. The Hannah Hoch–like juxtapositions of the artist’s [altered] face and the glamorous but disjunctive additions create troubling visages, ones that stare out insistently at viewers.

Throughout 2014–15, Nguyen hitchhiked around the United States in Across The American Plains, a durational performance/public intervention intended to help xe understand the underlying values of American society. The artist asked strangers if xe could live in their houses for a few days, knowing that people reveal their true selves in the intimacy of their homes. Nguyen photographed the sleeping surfaces xe was offered—beds, couches, and floors—as well as the landscapes xe traversed. The landscape photographs became a way “to suspend and sculpt time during moments of solitude, isolation, loneliness, and the thrall of nature on the journey.” Nguyen encountered a remarkable variety of experiences during that year, several of them life-threatening, and experienced racism, misogyny, white supremacy and xenophobic nationalism at close range.

When the artist’s family first moved to this country, Nguyen worked with xe’s mother and sister in a sweatshop that made T-shirts. At only 11 years old, Nguyen was tasked with cutting hanging threads from the almost-completed garments. Today, the artist creates “I Am That I Am,” a series of T-shirts that are branded with assertions of the cultural values identified in xe’s transcontinental travels. One shirt reads: I AM WHITE POWER. Another is limned with: I AM A BIGOT. The large red text is interspersed with smaller terms in white: HOMOPHOBIC and TRANSPHOBIC.

We often allow the slogans on our clothes to function as billboards announcing our identities. To wear a Nguyen T-shirt forces one to confront institutional biases in a very personal, embodied way.

Which, ultimately, is the goal of all Thinh Nguyen’s art.

Catch Thinh Nguyen at our panel discussion on Identity Art at Bermudez Projects, May 12. For more info click here.

0 Comments