Set on a six-acre site overlooking downtown Montgomery and, most significantly, the Alabama State Capitol, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opened in April 2018, is dedicated to the over 4,400 known victims of racial terrorism who were murdered by lynching in the years following Reconstruction up until 1950. The memorial goes further however, also addressing the humiliation of segregation, social injustice and police brutality, racial profiling and mass incarceration—all legacies of slavery—that continue into the present day.

A collaborative effort between the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) the Montgomery-based nonprofit organization founded by Social Justice activist and lawyer Bryan Stevenson and MASS Design Group, the memorial marries powerful emotion with striking design. EJI provides legal representation to people in prison who may have been wrongly convicted, or can’t afford effective representation, as well as those who may have been denied fair trials. MASS Design Group is an international collective of over 120 architects, landscape architects, engineers, industrial designers, writers, filmmakers and researchers. It believes in “expanding access to design that is purposeful, healing and hopeful.” In 2017, MASS Design Group received the National Design Award in Architecture by Cooper Hewitt, the Smithsonian Museum for Design.

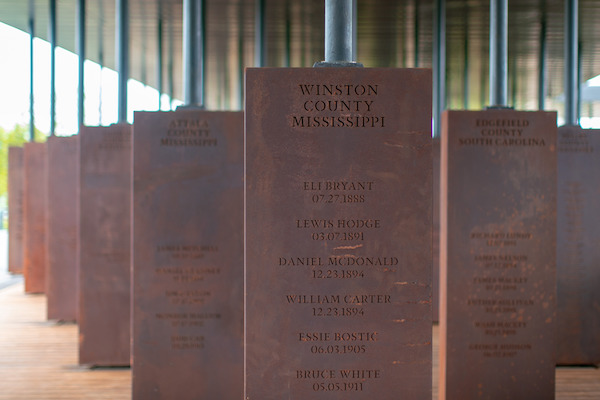

View of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, third corridor.

To enter the memorial, you go through a long, low covered walkway that leads into the open-air grounds. It’s a dramatic transition that serves to spotlight the main structure visible at the crest of the hill. From a distance, it resembles a modernist temple. Commanding, resolute; it has an austere grandeur that invites both awe and contemplation.

Walking up the path towards it, you pass Ghanaian sculptor, Kwame Akoto-Bamfo’s powerful Nkyinkyim installation. Charged with anguish and frantic movement, the sculpture holds nothing back. Its six African figures, stripped of everything except the loincloths they wear, convey the humiliation, agony and despair of slavery. The group is chained together in a coffle; their necks encircled with thick rings. On the ground lies a set of empty shackles, a kind of memento mori—we notice them and can’t help but wonder what it would feel like to have them on our wrists—what it would feel like to be those people. The restraints are rusty, which makes them stand out against the dark gray synthetic resin of the figures. Two of these figures, one male, one female, are on their knees, leaning forward as if they’ve been shoved or are being sick; another male squats unsteadily, a third seems to be crying out and struggling against his manacles. A standing female figure clutches a baby and reaches for a fourth male figure who is facing away from her, perhaps confronting the group’s captors. His aspect is proud, defiant and it’s as if she is trying to stop him and prevent him from causing what will surely be his doom.

Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, Nkyinkyim, at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Hank Willis Thomas’ Raise Up (2014) on the other side of the memorial, is equally arresting. The sculpture addresses police violence and social and legal injustice. Thomas offers a visual

synecdoche—bronze arms and heads, and in one figure, the upper part of his torso—to represent a row of 10 Black men, their arms raised in supplication, or surrender. Rendered with enormous sensitivity, Thomas captures the humanity of the men by distilling everything down to these expressive parts of the body. He sets them in a slab of concrete, creating the illusion that the men are drowning; it isn’t water that subsumes them, but the system that is stacked against them.

Continuing back by the entrance, texts providing U.S. slavery historical context are placed at intervals along the wall lining the path. The information is important, of course, but the texts serve another role, slowing your progress down; both physically and mentally, allowing you to process the experience. As you approach the main structure, you begin to notice its remarkable roof. More sculptural element than utilitarian cover, the steel framed roof clad in zinc metal panels is an open rectangle that frames the central quadrangle. It’s little more than a sliver, but dynamic in gesture: it suggests forward movement and power, like the wingspan of an airplane or the prow of a ship. It appears both heavy and weightless, resting on insubstantial-looking spindles set into what look like rectangular columns.

View of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Stepping into the shady interior, the atmosphere of solemnity intensifies as one is confronted by those “columns.” They’re actually rows of Corten steel blocks suspended by the spindles from the roof. There are more than 800 of these altogether. Measuring six feet in length, they have a human scale, suggesting bodies. Each block is inscribed with the location of a racial terror lynching and the names of those who were lynched. EJI’s original focus was 12 states in the Deep South, but that has been expanded to include lynchings that occurred in other states, as well.

In some cases, there is just one name; in others, there are many names. There’s a sense of profound intimacy as you come face-to-face with the blocks. Reading the names—names one would never know but for this memorial—make these individuals, and the acts that destroyed them, real. The size of the lettering changes depending on how many people are listed. The block for Carroll County, Mississippi has two columns to accommodate its 28 victims. The block that really stunned me was the one from Orange County, Florida. On just one day, November 3, 1920, a staggering 32 people, all but one, anonymous, were lynched. This lengthy list of victims conveys the frenzied terror of that particular day, which was an election day (100 years ago to the day of our upcoming presidential election). You realize that all those Black people were murdered for attempting to vote.

Detail of a “column” at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

As you proceed through the structure, the floor gradually slants down. But the blocks remain at the same height and so begin to rise off the ground emulating the hanging figures they represent. Eventually, they hang directly over the visitor. One is torn between admiring the stunning rhythmic pattern of the hanging blocks and the oppressive effect of passing beneath them. The weight of all that suffering, all that cruelty, hangs over you and, by extension, our nation, both literally and figuratively.

Rounding the second corner of the rectangle, one enters the third corridor, which features panels along the walls that tell the stories of over 90 men, women and children who were lynched, in every case for a trifling, or made-up transgression. Reading these descriptions is almost too much too bear. Heartbreaking doesn’t begin to describe it.

In the final corridor, a wall of water extending the entire length, is dedicated to the many anonymous victims of racial terror lynching. The rushing water, whether intentionally or not, is a soothing balm that alludes to the reassuring eternal continuum of nature.

View of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

At the center of the structure, a grassy mound is intended to suggest a gallows. Standing at the top, one is in the position of a person about to be lynched. But here, the crowd sitting in judgment is not a jeering hoard, but the silent dead represented by the Corten blocks.

Corten is a wonderfully earthy material which oxidizes serendipitously, imparting an individuality to the blocks, alluding to the individuality of those they represent. The rusty Corten also evokes Southern earth. Earth plays a potent role with samples gathered from lynching sites around the state of Alabama placed in glass jars that line a wall in the reception building. These are, in effect, reliquaries, each one bearing the name of the martyred victims and the location of their lynching. More earth from lynching sites around the country is placed in a large Lucite container placed in the final corridor of the memorial.

View of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Beyond the main structure duplicate blocks to the ones hanging within it are laid out. Resembling coffins lying in state, the sight of them underscores the vast number of lynching victims. As many blocks as there are, they only represent a fraction of the total as a great deal have more than one name inscribed on them. These duplicate blocks offer a powerful challenge to the counties where terror lynchings occurred to erect an historical marker that describes and memorializes the incidents that occurred. The message to those localities (and to all Americans) is clear: if we are ever to heal as a country where peace and justice prevail for all citizens, we must own up to our history of racial inequality. Thus far, 30 out of 805 counties have installed narrative markers at the sites of local racial terror lynchings.

Leaving Montgomery on I-65, a few miles north of town, we passed a giant confederate flag flying on the side of the highway. A sad reminder of where we are in this country—it was a major downer. Imagine leaving a holocaust site like Dachau or Auschwitz and after a short distance being confronted by a Nazi flag? For those who argue the Confederate flag is a symbol of heritage not hatred, I invite them to visit The National Memorial for Peace and Justice and see how they feel about that heritage when confronted with the facts the memorial lays bare.

0 Comments