When I talk with Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, his smiling face lights up the video conference window as he speaks of joy. He hopes to bring joy to the subjects of his portraits, and to those that view them. Picking up the range of tonality in Blackness, his portraits demand attention with a quiet yet confrontational gaze. He talks a lot about empowerment, which is registered in the stately and regal postures of his sitters, who appear before us like subjects in court portraiture.

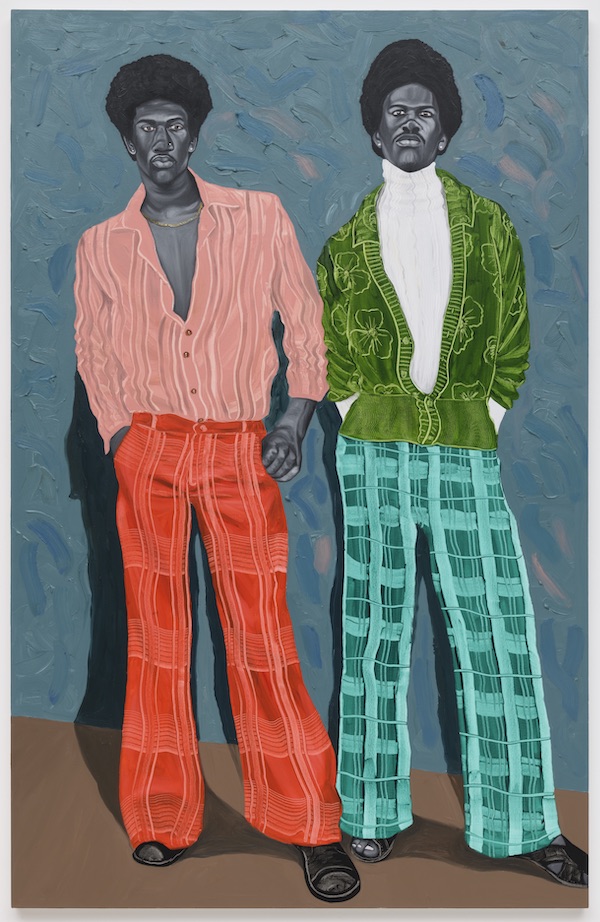

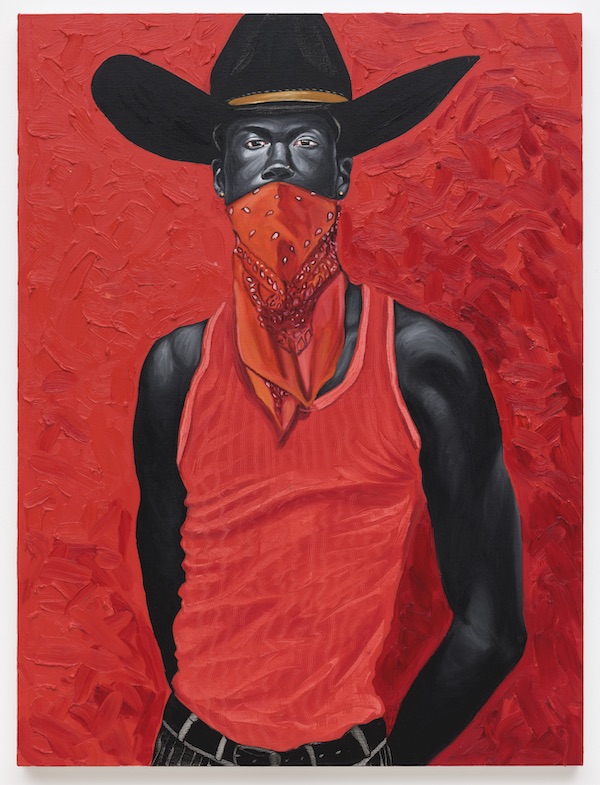

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Dapper, 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA

Hailing from Ghana, one of the fashion capitals of Africa that is known for its unique textile production, Quaicoe’s emphasis on clothing is strong. “Our textiles have names printed on the bottom, which are like proverbs, so when people are buying cloth they look at the proverb,” he says. “If that proverb doesn’t fit their character, they don’t buy it. They go for color, design—and also the proverb.” The significance of clothing in his work considers the beliefs to which we subscribe and how we express them in our clothing. Quaicoe wields this self-expression to make us question our own associations, particularly regarding color and gender. Central to his work is being an African in America, contemplating the ways in which we are the same and how we differentiate ourselves.

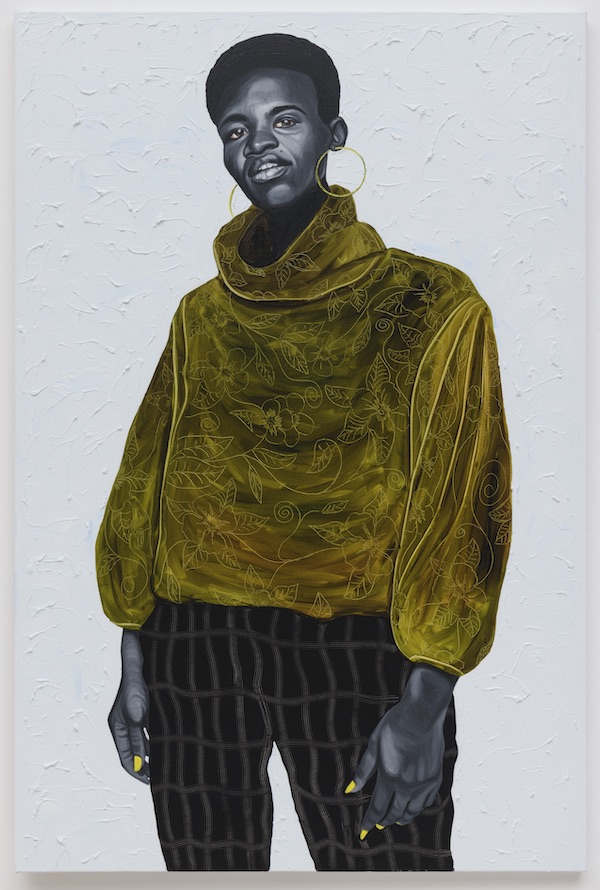

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Grace Osei, Green Nails, 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA

His entrée into art came from attending the movies and admiring the hand-painted film posters. After meeting an artist hanging their poster, Quaicoe asked if he could get some tutelage.

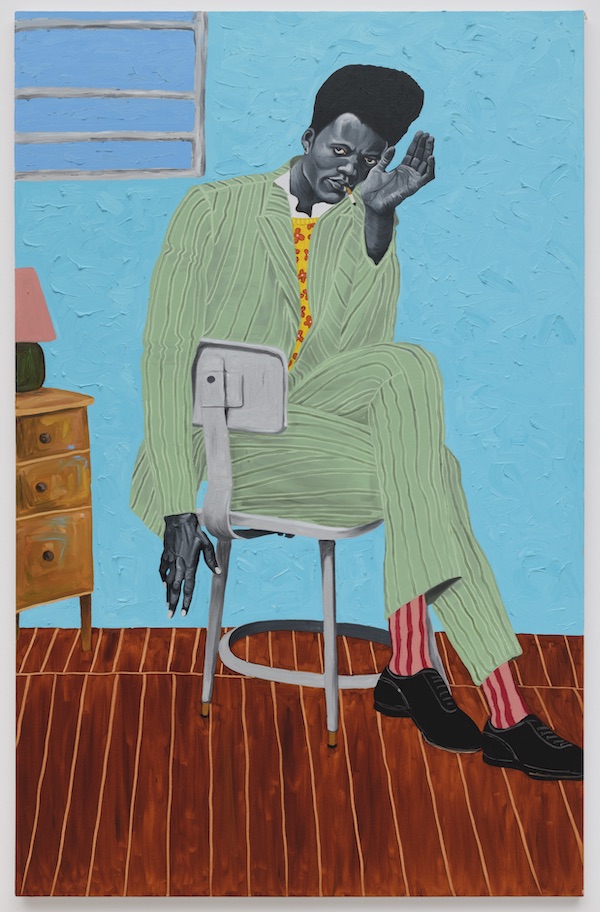

Storytelling is central to Quaicoe’s paintings, where characters hold the key. In addition to his subjects, Quaicoe’s inspirations come from listening to people’s conversations: “Everyone has their own life, their own story, if you listen.” Perhaps as a viewer, our role is to be silent for a moment, and listen to the stories the portraits silently tell us.

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe in his studio, Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA

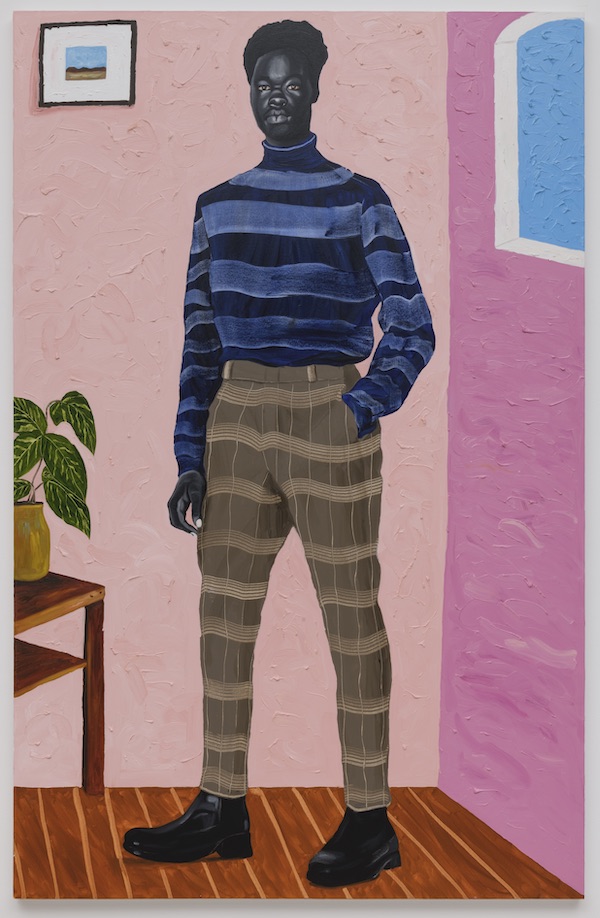

Quaicoe moved to Portland two years ago at 28. Overwhelmed by the differences in how Africans dressed compared to Black Americans, he points out, “It was very easy to spot who was from where; we [Africans] dress differently.” This notion of clothing as a cultural and personal signifier has persisted and (much like in court portraiture) aids in telling the story of the sitter. I wonder aloud whether these signifiers are in place to reveal or disguise the subjects of his paintings. Quaicoe smiles, speaking of the mystery of people, stating it likely does both—“You see what they want you to see.” This allows the subjects to have control over their projected perception, giving them a sense of empowerment.

Sometimes the choices—colors, even brands—feel so right that I am curious if his models are consciously styled. While Quaicoe does sometimes have an outfit in mind (and might request they wear it or add it to the painting later), it is always something he feels the person would wear anyway. He refers to it as being similar to a collage; he wants the painting to be harmonious, but only if it fits.

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Kwame Asare in Stripes, 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA

Quaicoe’s first solo exhibition in the U.S. was this past January with LA gallery Roberts Projects. It consisted of new portraits made while in residency at collector/artist Danny First’s La Brea Studios. While in LA, he met up with fellow painter Amoako Boafo (coincidentally a former classmate from Ghanatta College of Art and Design) who was represented by Roberts Projects at the time. Finding themselves in the same country again, the two reconnected and Boafo invited Quaicoe to come and share his studio in LA. It was here that Quaicoe met Roberts, who quickly responded to his work and suggested Quaicoe have an exhibition at his gallery.

Along with Boafo, Quaicoe looks to his contemporaries who paint representations of Blackness as his influences. Kehinde Wiley is a vital inspiration, particularly regarding depictions of empowerment and joy evinced in his portraits. He also cites Henry Taylor and Kerry James Marshall, as well as lesser-known photographers found via Instagram, which are sometimes used as reference for paintings.

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Joseph Cubo, 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA

Drawn immediately to the vibrant colors, shapes and styles, we read Quaicoe’s paintings slowly and are lured by the complexity in the subjects’ expressions. We question these figures’ perception of us. Quaicoe subjects are responsible for how they are seen.

Typically in portraiture, the viewer gains access to subjects who are depicted evocatively or vulnerably. However in Quaicoe’s paintings, one is halted abruptly by the textured painterly backgrounds that exist in stark contrast to the smooth striation in the bodies and faces of his subjects. We are met with the subjects’ Blackness, which is painted in gray scale. Nails, earrings, handbags and dressings are accented with color, indicating their intentional nature and suggesting their existence as a signpost. His subjects, with their knowing expressions, do not permit full entrance. The signifiers, at once disguising and revealing, confront the audience and challenge them to engage in a more slowly paced viewing that mimics the duration of getting to know someone. Often, this is precisely what happens.

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Bandana Coyboy, 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA

“When I first moved here [Portland] I had no friends, so if there was someone I thought was cool or that interested me I would ask to paint them; I still do that.” Through painting, Quaicoe is able to utilize his setting, the people in it and their selected symbols to orient himself in a new surrounding, something we are all doing every day. The title of Quaicoe’s Roberts Projects solo exhibition, ”Black Like Me,” was a reference to his experience of moving to Portland and noticing that, despite their notable cultural differences, the Black Americans he met were Black, like him, from the same race, the same family. The title is an empathic reference to a sense of shared pain and joy within the Black community. Those shown in this body of work, and his work in general, are neither subject or object; they are embraced in spirit and restored to power.

0 Comments